Modules and packages#

Learning goals

After finishing this chapter, you are expected to

understand what a module is

understand what a package is

import modules and packages in several ways

understand what a conda environment is and how to create and activate one

By now, you have already used packages: NumPy and Matplotlib. It is very likely that as you program more, you will use more and more packages. Not in this course, but probably as soon as you start on more complex projects. In this chapter we’ll explain a little bit more about modules and packages and how to properly use them in combination with Anaconda.

Note that there are no exercises in this chapter. However, if you want to understand a little bit more about what happens when you type conda install <package> in your terminal, you can find it here.

Modules#

A Python module is nothing more than a *.py file that you import and that defines variables and classes. This can be very convenient. For example, if you have written some functions or objects that you use in many different programming projects, you can put those functions in a module that you can easily reuse. Consider the contents of the following file, which we shall call mod.py. The module contains two variables, a function and a class.

s = "Hello world."

a = [100, 200, 300]

def foo(arg):

print('arg = {}'.format(arg))

class Foo:

pass

Now imagine that you want to use the function foo() in many different projects. If we have a different file, let’s say, project.py, and we want to use the function foo() in project.py, we simply to the following:

import mod

mod.foo("Test module")

The expected behavior is that now the function foo() will be called to output “Test module”.

To be able to import a module, it is very important that it can be found by Python. If you put the file in the same directory from which the script was called, you should be good. Alternatively you can put the module file in any other directory as long as it’s on your PYTHONPATH. This is an environment variable that points to the location of Python libraries. Modules/packages that you install in Anaconda are automatically on your Python path.

Importing modules#

The easiest way to use a module is by importing it via import <modulename> as we just did. It’s important to realize that - after importing - we cannot call all the functions in mod.py as if they are in project.py: we always need to prepend the module name and add a dot. For example, in the case above, calling foo("Test module") will not work because Python does not understand what you mean with foo(). Instead, we have to explicitly use mod.foo("Test module") so that Python will actually use the foo() function from the mod module.

Alternatively, we can import parts of the module directly, but that means that any other function, variable or class with the same name that we would have in our current *.py file get overwritten. To achieve this, we would use from mod import foo instead of import mod. Now, we can use foo("Test module") instead of mod.foo("Test module"). If you’re absolutely confident that you want to import everything from a module and don’t want to bother with prepending module names, you can also use from mod import *. The * commonly means ‘everything’ in programming.

One more thing that you can do, is import a function, variable or class directly, but give it a different name for greater ease. In this case, you could use from mod import foo as bar and in the project.py script call bar("Test module"). You can use any term, here bar is just an alias. Similarly, you can import entire modules under alternate names: import mod as modest.

Packages#

A package in Python is a collection of several modules that can be accessed via dot-notation. For example, you have used the Matplotlib package, which has a Pyplot module matplotlib.pyplot. Packages can either be imported in full, or separate modules can be imported. Importing a package works similarly as importing a module, and in pratice you will likely not notice the difference.

How to install modules or packages#

There are multiple ways to manage or organize your packages in Python. Typically you’ll use pip, the standard Python package manager, or Anaconda. Anaconda has a couple of advantages over pip in the way that it manages packages, which is why we advice you to use it. Anaconda comes with >100 pre-installed packages that might come in handy, so you don’t have to install every package from scratch.

For many packages, you can use

conda install <package_name>

to install the package, where <package_name> is the name of the package that you want to install.

You might have already done this once or twice in the previous chapters.

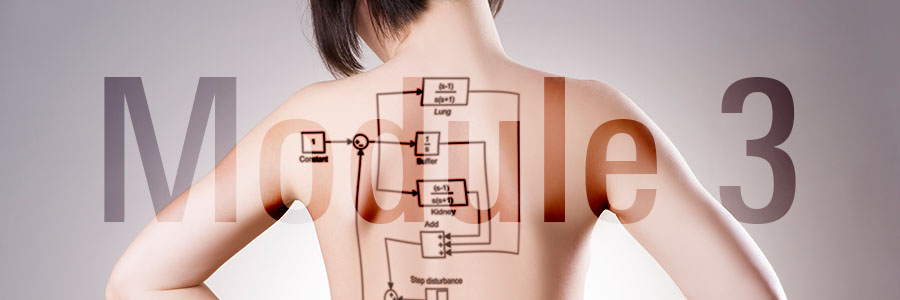

Dependencies#

Very few - if any - packages in Python are completely independent from other packages. You will see that packages or modules typically import functionality from other packages and modules. If package A is dependent on package B to work, we call package B a dependency of A. Dependencies often take on the form of a tree or graph and one package can be directly and indirectly dependent on many packages. Things can get complicated when packages have different versions. As most code in Python is under constant development, new versions of packages get released all the time. This also holds for Python itself, whose most current version (in January 2024) is v3.12.1. Things can get real complicated real quickly. For example, the below graph visualizes the dependencies of the six package. You can see that versions of some packages should be higher than or equal to a particular version (>=), while others should not be of a particular version (!=) for this package to be used.

Anaconda environments#

You can probably imagine that if you want to install ten different packages to run your code with, there can be conflicts between dependencies. For example, for package A some dependency should have at least a particular version, while for package B that version is not supported. One of the reasons to use Anaconda as your package manager is that it automatically tries to resolve these conflicts. Anaconda performs dependency management and will look for versions that are compatible with packages that you have already installed. If it is impossible to solve this puzzle, it will also tell you.

However, the more packages you install, the higher the chance becomes that there will be some version conflicts that cannot be resolved. That’s why it’s always smart to work with environments. An environment in Anaconda is a directory that contains a specific set of packages that you have installed. You could for example make an Anaconda environment for this course, and a different environment for some other course where you use other packages and dependencies. The Anaconda website contains excellent documentation on how to properly set up environments. We’ll here show you the basics.

Creating an environment#

You can create an environment by typing

conda create --name <myenv>

where <myenv> is the name of your environment. For example, to create an Anaconda environment for this course, go to your command line interface (Anaconda prompt on Windows) and type

conda create --name module3

If you want an Anaconda environment with a particular Python version, you have to provide that version when creating the environment. For example, to set up an environment with Python version 3.12.1, do the following

conda create --name module3 python=3.12.1

Note that a new ‘clean’ environment does not contain all the packages that your default - base - Anaconda environment contains. To avoid clutter, only the bare minimum of packages is installed for a new environment. To use additional packages, you will have to install them yourself once you’re in the environment. Alternatively, you can add particular packages (and their versions) that you want to install immediately

conda create --name module3 python=3.12.1 numpy=1.26.3 scipy

If you have a long list of packages that are required, or you want users of your Python code to use exactly the same packages that you do, you can use an environment.yml file. This is simply a list of packages and versions that should be installed. This is a bit more advanced and is explained in more detail here. One great feature of Anaconda is that you can also make this file automatically based on your currently used packages. By running conda env export > environment.yml, you can create an environment.yml file with the exact packages that you are currently using in your active environment.

You can always get a list of all your Anaconda environments by typing conda env list. Note that by default there is a base environment. This is the environment that you have been working in so far.

Activating and deactivating environment#

Once you have created your environment, you can activate it using

conda activate <myenv>

where again <myenv> is the name of your environment. Now, you are in the environment and anything you do (like installing packages) will only affect that environment and not your global environment.

You can usually see in your terminal which environment is active.

To ‘leave’ an environment, you can deactivate it using conda deactivate.

VS Code and environments#

VS Code will recognize Python interpreters within conda environments. Hence, when you have created a new conda environment, it should automatically appear in the list of Python interpreters that you can select to run your Python scripts or Jupyter notebooks in VS Code.